Two weeks ago there was a flurry of public comment across Australia and the United Kingdom on the value and risks of meta-analysis and synthesis of meta-analyses in education research. Given that synthesis of meta-analysis underpins the information presented in the Teaching & Learning Toolkit (the Toolkit), Evidence for Learning thought it would be useful to contribute to the discussion.

In her measured and thoughtful post, Deb Netolicky, Research Lead at a school in Western Australia, laid out several of her own reservations about the Toolkit and summarised some wider objections to meta-analysis as a useful tool in education research. As Deb pointed out in her post, she and I have had the opportunity to discuss the Toolkit directly, and I welcome the opportunity to extend the discussion here in the public realm and invite others to join.

The number of reservations Deb raises are too many to cover in one article, so Evidence for Learning will respond in a three part series of articles, starting with one of them here and responses on the other reservations to follow relatively quickly in another two articles.

How schools might use the Toolkit

One key reservation is that schools may approach the Toolkit without the necessary caution. In her concluding sentence, Deb writes, ‘If Australian organisations and schools are to embrace the E4L Toolkit as part of their pursuit of having a positive impact on learners and more systematic bases on which to make decisions, I hope they do so with a cautious step and a critical eye.’

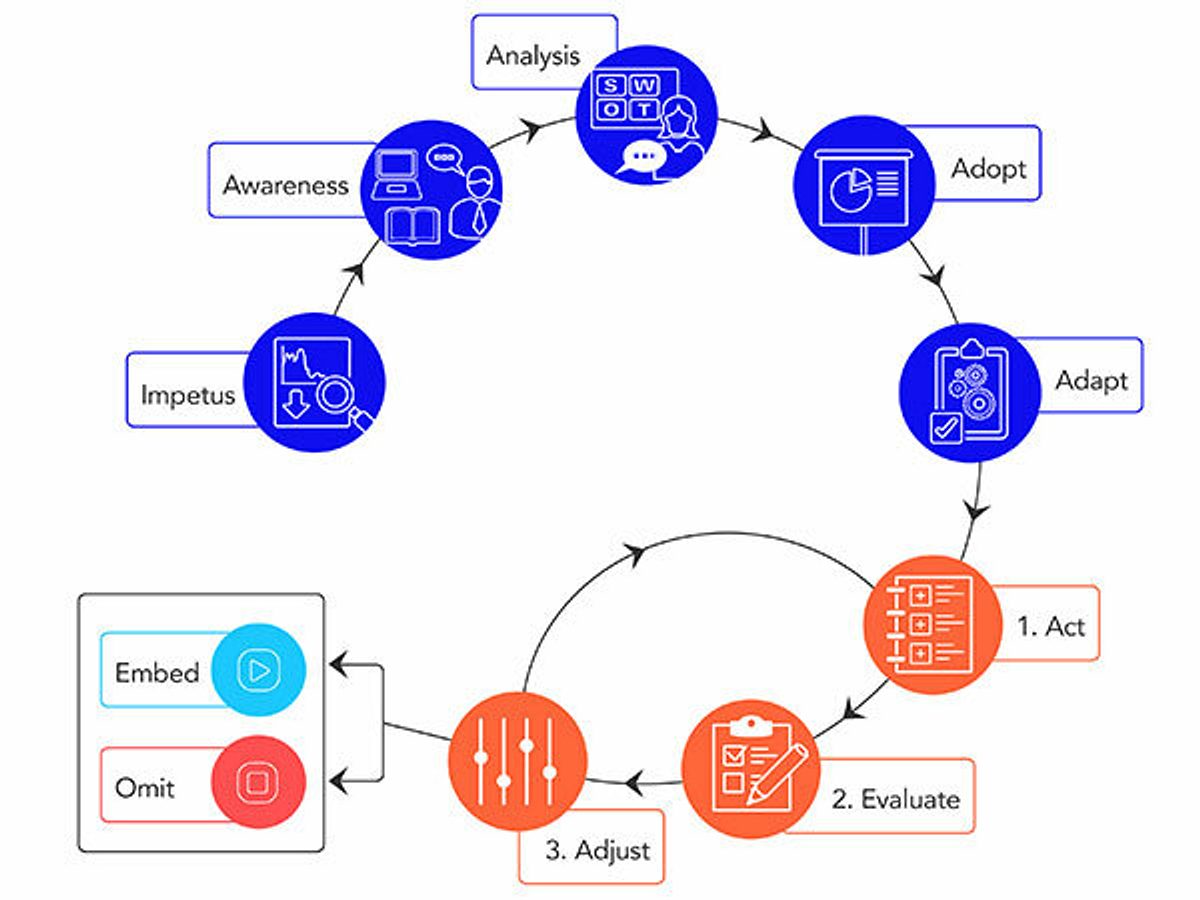

Evidence for Learning agree entirely. We do not envision the Toolkit as a resource that should dictate or direct professional decisions in schools. Instead, we hope school leaders and teachers will use it to start discussions with their peers and to help inform their professional judgement with research evidence. This is why we have articulated an Impact Evaluation Cycle, which describes key steps schools may go through when identifying a problem of practice, deciding on a course of action, and assessing its impact. Of course, many schools deliberately work in with cycles like this already. In the context of this kind of disciplined decision-making in schools, we hope that, in its format, the Toolkit reduces schools’ barriers to initially engaging with research evidence and, in its content and language, encourages a nuanced reading of the evidence to inform their decision-making.

In this vein, it’s important to call particular attention to two features of the Toolkit.

1.) Padlock ratings

These ratings provide a summary of the strength of the evidence underpinning the estimate of impact in the months’ progress rating. This strength is not just down to how many studies are included, but their quality, as well. (See full explanations in the Evidence Security at About the Toolkit.)

For the months’ progress rating to receive five padlocks, for example, there must be ‘consistent high quality evidence from at least five robust and recent meta-analyses where the majority of the included studies have good ecological validity and where the outcome measures include curriculum measures or standardised tests in school subject areas.’ For an approach receiving only two padlocks, though, there is only ‘at least one meta-analysis or systematic review with quantitative evidence of impact on achievement or cognitive or curriculum outcome measures.’

Knowing these differences, school leaders can make nuanced readings of the evidence. For example, a school leadership team might be considering whether to introduce small-group tuition or behaviour interventions to improve outcomes for a group of struggling students (on average, both approaches yield four month’s additional progress). If they note that the evidence for behavioural interventions is much more extensive and of higher quality than that for small-group tuition, this may influence their decision about what type of approach to explore further. Of course, this decision would also be influenced by factors in their local context. They know their students.

2.) Careful language

Another key feature of the Toolkit that encourages nuanced understanding is the careful language used in the more detailed information for each approach. In Dan Haesler’s comments on the Toolkit in the 5 March 2017 episode of the Teachers’ Education Review Podcast, he expressed concern that the Toolkit might lead to us oversimplifying the debate about which educational approaches might be appropriate for a given context. He also noted that, while he may have been a victim of a click-bait tweet (‘The 10,000 pieces of evidence that will settle the homework wars’), words included in the Toolkit information for homework (primary) such as ‘some’ and ‘limited’ to describe the underlying evidence point to far more nuance than words like ‘settled’. The vagaries of media coverage notwithstanding, the language in the Toolkit pages is carefully chosen so as not to make unjustified claims about the underlying evidence. The qualifying language can help schools understand whether an approach may be particularly useful for their context and to what extent they can be confident in the articulated findings.

To follow Dan’s example of primary homework, the Toolkit page reads, ‘There is some evidence that when homework is used as a short and focused intervention it can be effective in improving students’ achievement, but this is limited for primary age students.’ Reading this, a primary school leadership team considering a new homework policy to improve student academic achievement would understand that (1) the evidence here is not settled but (2) what evidence there is indicates that homework should be short and focused. Given this, they might decide to put their effort into something relatively more likely to have an impact or, if they did decide to implement homework where they hadn’t before, to limit its length.

These features are consistent with our view that any school-based improvements in educational outcomes will be the results of the considered professional decision-making of school leaders and teachers. Like Deb, Evidence for Learning hope that they approach their work, and ours, ‘with a cautious step and a critical eye.’

We’ll return in our next two articles in this series to address other reservations and criticisms of meta-analysis and synthesis of meta-analyses.

John Bush is the Associate Director of Education at Social Ventures Australia and part of the leadership team of Evidence for Learning. In this role, he manages the Learning Impact Fund, a new fund building rigorous evidence about Australian educational programs.