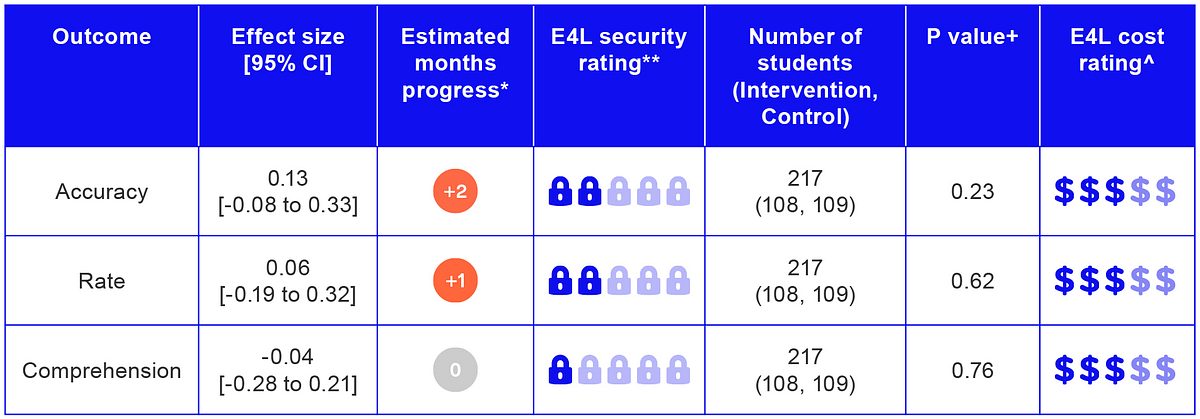

Note: The security rating and months’ impact for this study are individually rated for the findings of each YARC‑PR’s Primary Outcome (see Research Results section below).

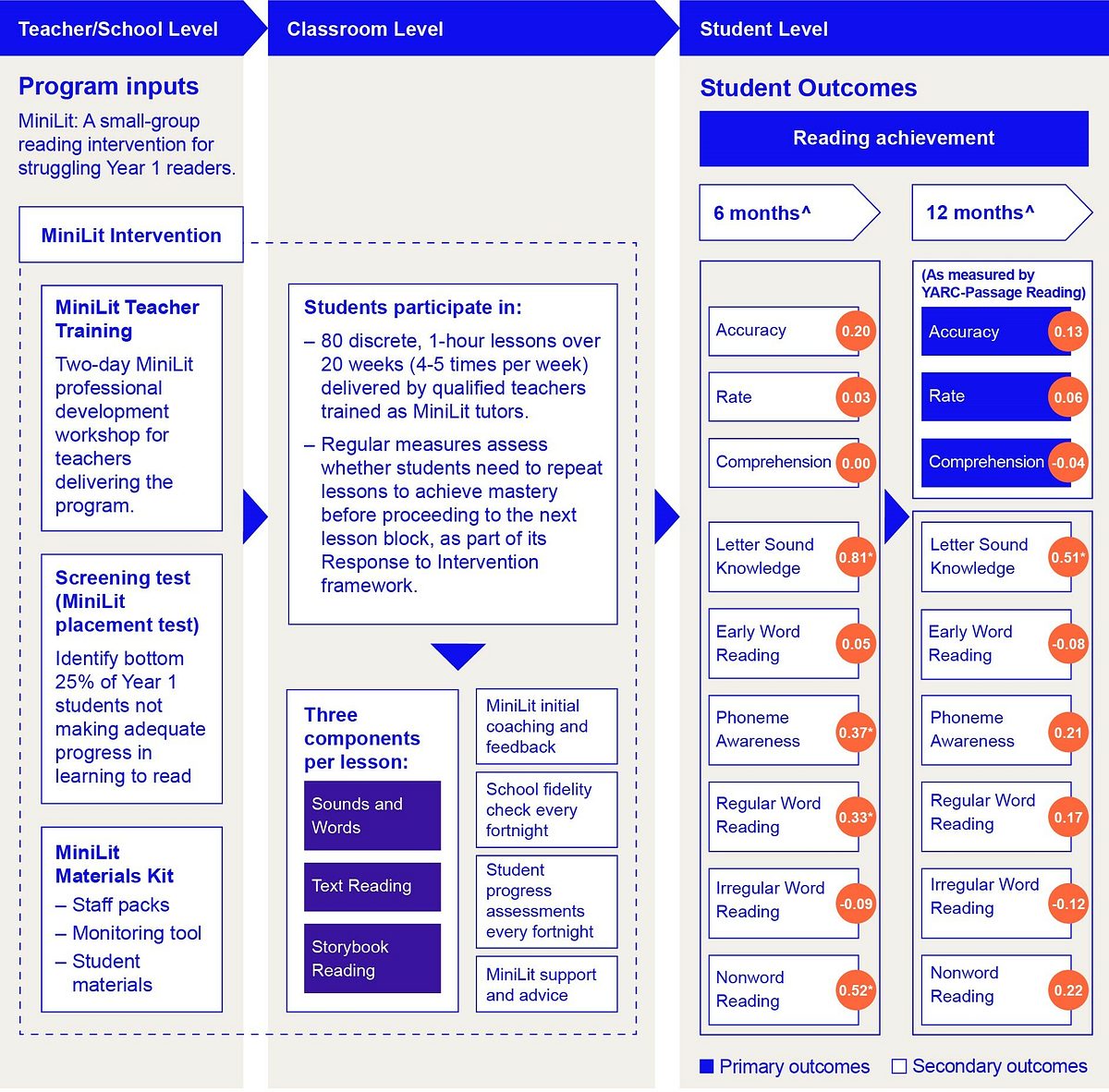

MiniLit is an early literacy intervention for struggling Year 1 readers, which aims at improving five literacy skills of (1) Phonemic Awareness, (2) Phonics, (3) Fluency, (4) Vocabulary and (5) Comprehension, particularly the first three. The evaluation was conducted as a randomised controlled trial to evaluate whether the early reading intervention had a greater impact on reading than students receiving Usual Learning Support, which could include whole-class approaches and/or support programs for struggling readers (the control group).

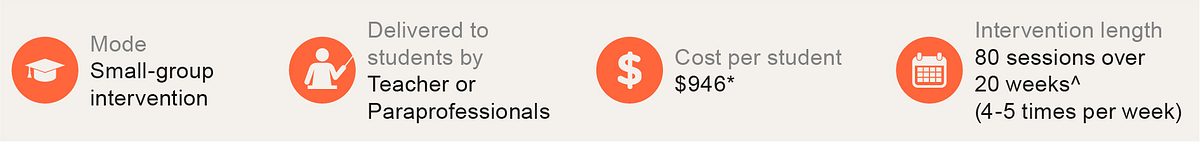

MiniLit is designed as an 80-session intervention (four-five times a week) delivered in small groups (of up to four students) with students identified to be in the bottom 25% of readers in Year 1. Delivered by teachers and paraprofessionals trained as MiniLit tutors, the intervention consists of 80 unique lessons. Students are assessed fortnightly to repeat lessons if necessary, to achieve mastery before proceeding to the next lesson block.

This trial tested MiniLit in a 20-week intervention period. The evaluation was funded as an efficacy trial. 217 students from nine schools in the greater Sydney and Newcastle area participated in the trial from November 2016 to June 2018.

This randomised controlled trial found that MiniLit, as experienced in this trial, did not have an additional impact on reading, as measured by the YARC – Passage Reading1 (YARC-PR) tests on Accuracy, Rate and Comprehension but there was evidence of significant improvements in foundational reading skills at six months2, particularly Letter Sound Knowledge which was also sustained at 12 months. These findings on the three primary outcomes have a low security rating and need to be treated with caution given uncertainty about the YARC-PR measure and the level of change this trial was set up to detect.3

There appear to be greater gains for students who had greater exposure to MiniLit. Students who received the minimum recommended attendance of 80 per cent, that is at least four days per week on average, during the 20-week intervention period appear to have made strong improvements in Reading Accuracy and in foundational reading skills at both six and 12 months. However, it is important to note that only slightly over half of the students (65 students or 55%) received the minimum 80 per cent recommended attendance in this trial (i.e. at least four times a week). Sixteen students (13%) received 40 per cent or less (less than two days per week) of MiniLit lessons. The implications of this variation are discussed in the evaluation report.

Evidence from the process evaluation found that schools faced difficulties implementing MiniLit four or five days per week over 20 weeks due to school resource constraints and student absences. Schools value the program and the benefits of MiniLit’s Sounds and Words component in supporting struggling early readers. However, they reported challenges in comfortably covering the content of all three activities (Sounds and Words, Text reading and Storybook reading) within each one-hour lesson. Schools should consider a longer intervention time for students to complete all MiniLit lessons and in allowing adequate time each day to complete all three of the MiniLit activities, which may require more than the recommended hour.

Subject area: Literacy

The logic model below reflects the Primary and Secondary outcomes of the evaluation with the effect size results.

*Indicates statistically significant effect (p<0.05).

^In this study, Outcome Assessments were completed immediately post-intervention (approximately six months post-randomisation) and six months post-intervention (approximately 12 months post-randomisation).

*Refer to Appendix A of Report used to translate effect size into estimated months progress.

**Refer to Appendix B of Report for E4L independent assessment of the security rating.+Evidence for Learning has developed a plain English commentary on statistical significance to support readers in interpreting statistical results in our reports.

^The E4L cost rating is an average of the cumulative cost of implementing the program over three years. The significant cost is incurred in the first year and once established, the recurrent cost of MiniLit in terms of consumables per student is $72 for student books and testing and record books.

The project involved nine primary schools located in the greater Sydney/Newcastle area with socio-economic status in the top two quartiles4 (indicating highest levels of disadvantage). A total of 237 students from nine schools participated, of which 119 students were allocated to the MiniLit group and 118 students to the control group. This evaluation is supported by the NSW Department of Education.

*The significant cost is incurred in the first year and once established, the recurrent cost of MiniLit in terms of consumables per student is $72 for student books and testing and record books.

^Students receive 80 unique lessons as they are assessed fortnightly and repeat lessons if necessary to achieve mastery before proceeding to the next lesson block.

The cost of the MiniLit program delivered by MiniLit tutors (teachers and paraprofessionals) is moderate at $946 per student (approximate cost per student averaged over three years). The bulk of the costs is incurred in the first year ($11,210) which includes training, materials and staff time to deliver the intervention to four students for two terms over three years. The recurring cost of MiniLit per student is $72.

Key conclusions

- For the intention to treat analysis (which includes all students enrolled in the study irrespective by their assigned groups), there was no strong statistical evidence that MiniLit led to better student reading at 12 months compared to students receiving Usual Learning Support, as measured by YARC – PR Reading Accuracy (effect size = 0.13, [-0.08 to 0.33, p=0.23]), Reading Rate (effect size = 0.06, [-0.19 to 0.32, p=0.62]) and YARC – PR Reading Comprehension (effect size ‑0.04, 0.28 to 0.21, p=0.76]). These were measured using the York Assessment of Reading Comprehension – Passage Reading. However, a large number of intervention and control students performed at the floor for the measure at the outcome time point, with nearly all not being able to complete the measure at baseline. Therefore, the findings should be considered with caution.

- On the secondary outcomes which measured early reading skills, there was statistical evidence that, compared to the Usual Learning Support group, students in the MiniLit group made positive gains in Letter Sound Knowledge, which is a foundational reading skill for reading. At six months, there was strong statistical evidence that the MiniLit group scored higher on tests of Letter Sound Knowledge, Phoneme Awareness, Regular Word Reading, Nonword Reading and Accuracy as measured by the YARC – Early Reading and the Castles & Coltheart‑2 assessments. At 12 months, the differences between groups were smaller, with only Letter Sound Knowledge having strong statistical evidence of being higher in the MiniLit group.

- Compliance was defined as students receiving the intervention for at least four days per week over the 20-week intervention period, as defined by the program developers. When considering the students who did meet the recommended number of lessons (i.e. 80 lesson out of a possible 100 school days, 4 days per week) there was strong statistical evidence that MiniLit students scored higher on tests of Letter Sound Knowledge, Phoneme Awareness, Regular Word Reading and Nonword Reading at both six and 12 months, as well as Accuracy at six months. However, it is important to note that nearly half of the students did not receive the intervention for at least 4 days per week. Of the 119 students involved, 65 (54.6%) had minimum 80 per cent or more (4 or more days per week), 38 (31.9%) between 60 – 80 per cent (e.g. 3 days per week), and 16 (12.6%) had 40 per cent or less (e.g less than 2 days) during the 20-week period. It is unknown whether this was due to available resources (i.e. staff not working full-time) or if schools perceived the intervention cannot be delivered for at least 4 days per week.

- Implementation fidelity is critical to the effectiveness of a program. Strong statistical evidence showed that when there was high implementation fidelity, student outcomes were better in Letter Sound Knowledge, Phoneme Awareness and Nonword Reading. In particular, there was strong statistical evidence that higher fidelity was associated with higher secondary outcomes at six months and with higher reading accuracy at 12 months.

- MiniLit teachers valued the initial coaching provided by MiniLit in providing feedback to improve specific activity. However, they reported difficulties completing the three MiniLit activities (Sounds and Words, Text Reading, Storybook Reading), within the recommended one-hour MiniLit lesson. More access to the Text Reading and Storybook Reading activities may contribute to better student results on the primary outcomes.

- The process evaluation highlighted some key considerations. Schools should allow enough time for students (i.e. three school terms) to complete all MiniLit lessons, especially given that some schools may find it difficult to implement MiniLit for four or five days a week due to school resource constraints and student absences. Schools should also allow for adequate time each day for students to complete all three of MiniLit activities, which may require more than the recommended hour.

- Future research could examine whether a longer intervention time that enables students to complete the whole MiniLit intervention will lead to more positive student outcomes. In addition, it should aim to follow children for a longer period of time, enabling an understanding as to whether benefits in the early reading skills can be consolidated and students become more skilled readers.

Evidence for Learning has provided its own plain English commentary on implications based on the evaluation findings and considerations for schools and systems.

MiniLit E4L Commentary

Uploaded: • 454.5 KB - pdfMultiLit, the developers, have published their own statement in response to the Evaluation Report. For transparency for readers we provide a link to their statement below.

MultiLit statement is here. This statement does not form part of Evidence for Learning’s reporting for this Project.

The following ‘practitioner-friendly’ reports are free to access and download.

MiniLit Evaluation Protocol

Uploaded: • 720.2 KB - pdfMiniLit Evaluation Report

Uploaded: • 2.8 MB - pdfMiniLit Executive Summary

Uploaded: • 493.6 KB - pdfThis evaluation report and supporting materials are licensed under a Creative Commons licence as outlined below. Permission may be granted for derivatives, please contact Evidence for Learning for more information.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Licence.

1. The YARC-Passage Reading was agreed as the designated primary outcome measure for this study when the trial was first designed. However, a majority of children in this study were not able to complete the primary outcome measure at baseline due to the level of difficulty and at the follow-up time point.

2. In this study, Outcome Assessments were completed immediately post-intervention (approximately six months post-randomisation) and six months post-intervention (approximately 12 months post-randomisation).

3. This trial was powered to achieve a Minimum Detectable Effect Size (MDES) of 0.37 at randomisation, which meets E4L’s three padlock rating for MDES of <0.4.

4. Based on NSW Family Occupation and Education Index (FOEI) scores, schools with high FOEI scores in Quarters 1 and 2 are identified as relatively disadvantaged (around 91 per cent of students on average for schools with FOEI scores close to 200). https://www.cese.nsw.gov.au//images/stories/PDF/FOEI_Technical_Paper_final_v2.pdf